Greetings everyone,

If you have not already experienced it, any day now, your ears will be met with the screams of millions of periodical cicadas. While every year we experience the evening songs of the annual cicadas, this year we are privileged to hear the musical musings of cicadas from the Great Southern Brood. This periodical brood, also known as Brood XIX (Brood 19), is one of only three surviving broods with a 13-year cycle.

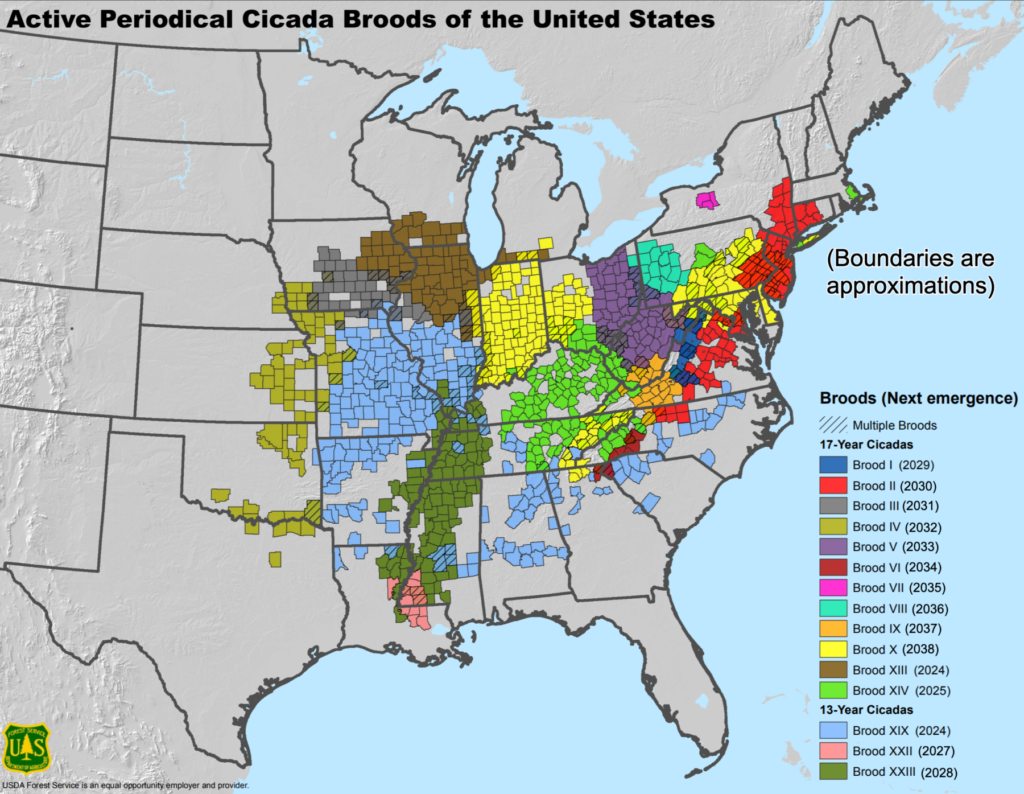

In 2021, North Georgia was on the southern tip of Brood X’s (a 17-year life cycle brood) distribution, so a few counties experienced the pandemonium of that brood in 2021 (see the yellow in map below). However, Brood XIX is expected to cover several more counties, reaching nearly to middle Georgia (see the light blue in map below).

While the hullabaloo might seem hellacious to many, periodical cicadas are truly a remarkable event. The nymphs (‘babies’) of Brood XIX periodical cicadas have lived below ground for 12 years and 11 months, feeding on the sap from deciduous plant roots (since 2011!). Now, after almost 13 years of being underground, within the next month all these cicada nymphs will crawl from the soil, climbing tree trunks or any other structure, and emerge from their nymphal skins (leaving their exuviae or ‘shells’ behind). The next day, the newly emerged males will fly to the tree tops and begin their chorus of mating songs to attract the females. Amazingly, periodical cicadas are found only in the eastern U.S. and nowhere else in the world. And while they might look menacing with their black bodies and red eyes, cicadas cannot bite or sting and they are not poisonous, making them perfectly harmless.

To a bug nerd like myself, this surely sounds (no pun intended) like an amazing event. However, as someone who works in agriculture, I also understand that you might be asking, “with millions of the cacophonous creatures emerging during the next month, will they damage my grape vines?“

Unfortunately, this is a tough answer. The short answer is, “maybe.” Cicada nymphs will feed on the roots of grape vines, which can definitely reduce vine vigor, but the more immediate risk is due to the females laying eggs in the new shoots, cordon, or even the trunk, which can cause the vine to dieback. The rule of thumb is to not plant anything during a ‘brood’ year for cicadas, but obviously the real world doesn’t work like that. As such, Doug Pfeiffer at Virginia Tech recommends wrapping netting around young vines to help stop female cicadas from laying eggs in the vines. Alternatively, he has also suggested wrapping the trunks of young vines with aluminum foil to protect them from egg laying. Seems like a lot of work, but if a new vineyard is in a high cicada area, it might be worth it. A more conventional approach to protect the vines would be to apply a broad spectrum (like a pyrethroid) insecticide, particularly to the base of the vines once the cicadas are active. While there are no chemicals that are labeled for use on cicadas in vineyards, cover sprays for other key insect pests should also help suppress any cicadas that might be hanging out in the vineyards.

The silver lining of cicada emergence, particularly with these periodical cicadas, is that their distribution across the state is patchy. Looking at the map above, scientists can only predict which counties Brood XIX are going to be found in based on the distribution from 13 years ago. Even back then Brood XIX cicadas were not necessarily widespread throughout all those counties. In addition, a lot can happen in 13 years, so many of the nymphal cicada’s likely will not make it to adulthood. As such, it difficult to predict where they are going to be. If a large population of periodical cicadas emerge in a forest next to a newly planted vineyard, then those young vines are going to be at a risk, whereas if there are no cicadas nearby, then obviously there is going to be minimal risk.

So while I don’t have the perfect answer, I am hopeful that the grape industry in Georgia is not going to be at risk from Brood XIX. Hopefully we can just marvel at the magnificent melody that these bizarre and amazing creatures produce this year.

And if you are really adventurous, Nancy Hinkle (UGA’s esteemed Veterinary Entomologist) suggests eating the cicadas. She says, “Humans can eat cicadas; they’re like softshell crab. So it is important to harvest them while they are still soft, before their skin hardens. Go out very early in the morning, before dawn, and collect newly-emerged adults that have just come out of their nymphal skins. Remove the legs and wings. Sautee them in garlic butter and serve hot. Recipes can be found online.” To each his own 😉

Have a great season everyone!